Serial Vs Parallel Dilution

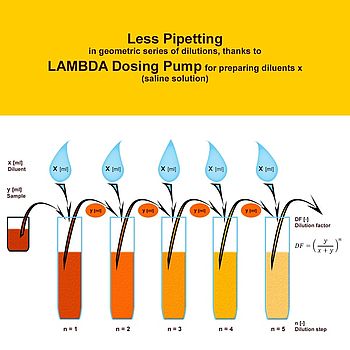

A serial dilution is the stepwise dilution of a substance in solution. Usually the dilution factor at each step is constant, resulting in a geometric progression of the concentration in a logarithmic fashion. A ten-fold serial dilution could be 1 M, 0.1 M, 0.01 M, 0.001 M. When do I use the serial dilution technique instead of the parallel dilution technique? Another way to make dilutions is to use some of your existing stock solution to make a dilute solution, then use some of the dilute solution to make an even more dilute solution, then use some of that solution to make an even more dilute solution, and so on.

This section is not a recipe for your experiment. It explains someprinciples for designing dilutions that give optimal results. Onceyou understand these principles, you will be better able to designthe dilutions you need for each specific case.

Often in experimental work, you need to cover a range ofconcentrations, so you need to make a bunch of differentdilutions. For example, you need to do such dilutions of thestandard IgG to make the standard curve in ELISA, and then againfor the unknown samples in ELISA.

You might think it would be good to dilute 1/2, 1/3, 1/10, 1/100.These seem like nice numbers. There are two problems with this series ofdilutions.

- The dilutions are unnecessarily complicated to make. You need to do a differentcalculation, and measure different volumes, for each one. It takes a longtime, and it is too easy to make a mistake.

- The dilutions cover the range from 1/2 to 1/100 unevenly.In fact, the 1/2 vs. 1/3 dilutions differ by only 1.5-fold in concentration,while the 1/10 vs. 1/100 dilutions differ by ten-fold. If you are going tomeasure results for four dilutions, it is a waste of time and materialsto make two of them almost the same. And what if the half-maximal signaloccurs between 1/10 and 1/100? You won't be able to tell exactly where itis because of the big space between those two.

Serial dilutions are much easier to make and they cover the range evenly.

Serial dilutions are made by making the same dilution step over and over,using the previous dilution as the input to the next dilution in each step.Since the dilution-fold is the same in each step, the dilutionsare a geometric series (constant ratio between any adjacent dilutions).For example:

- 1/3, 1/9, 1/27, 1/81

- 1/5, 1/25, 1/125, 1/625

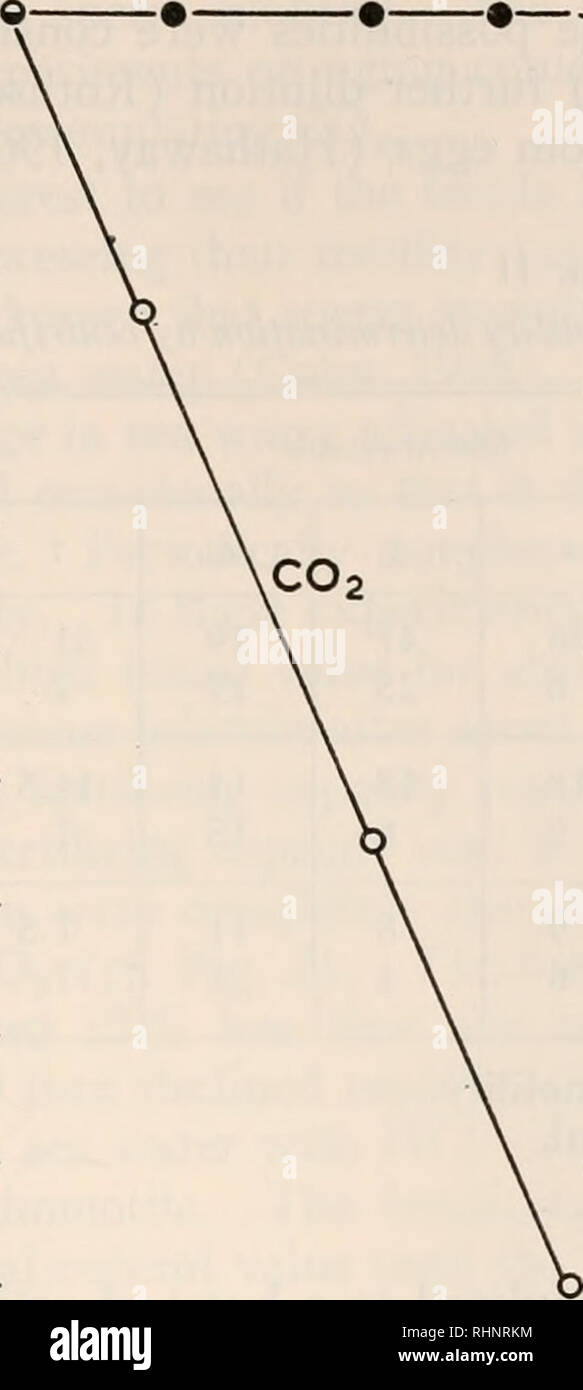

When you need to cover several factors of ten (several 'orders of magnitude') witha series of dilutions, it usually makes the most sense to plot the dilutions(relative concentrations) on a logarithmic scale. This avoids bunching mostof the points up at one end and having just the last point way fardown the scale.

Before making serial dilutions, you need to make rough estimatesof the concentrationsin your unknowns, and your uncertainty in those estimates. For example,if A280 says you have 7.0 mg total protein/ml, and you thinkthe protein could be anywhere between 10% and 100% pure, then yourassay needs to be able to see anything between 0.7 and 7 mg/ml.That means you need to cover a ten-fold range of dilutions, or maybe a bitmore to be sure.

If the half-max of your assay occurs atabout 0.5mg/ml,then your minimum dilution fold is(700mg/ml)/(0.5mg/ml) = 1,400.Your maximum is(7000mg/ml)/(0.5mg/ml) = 14,000.So to be safe, you might want to cover 1,000 through 20,000.

In general, before designing a dilution series, you need to decide:

- What are the lowest and highest concentrations (or dilutions)you need to test in order to be certain of finding the half-max? Thesedetermine the range of the dilution series.

- How many tests do you want to make? This determines the size of theexperiment, and how much of your reagents you consume. More tests will coverthe range in more detail, but may take too long to perform (or cost too much).Fewer tests are easier to do, but may not cover the range in enough detailto get an accurate result.

- What volume of each dilution do you need to make in order to haveenough for the replicate tests you plan to do?

Now suppose you decide that six tests will be adequate (perhapseach in quadruplicate).Well, starting at 1/1,000, you need five equal dilution steps (giving yousix total dilutions counting the starting 1/1,000) that end ina 20-fold higher dilution (giving 1/20,000). You can decide on a goodstep size easily by trial and error. Would 2-fold work? 1/2, 1/4, 1/8, 1/16, 1/32. Yes, in factthat covers 32-fold, more than the 20-fold range we need. (The exact answeris the 5th root of 20, which your calculator will tell you is 1.82 foldper step. It is much easier to go with 2-fold dilutions and gives about thesame result.)

So, you need to make a 1/1,000 dilution to start with. Then you need toserially dilute that 2-fold per step in five steps. You could make 1/1,000 byadding 1 microliter of sample to 0.999 ml diluent. Why is that a poor choice?Because you can't measure 1 microliter (or even 10 microliters) accuratelywith ordinary pipeters. So, make three serial 1/10 dilutions(0.1 ml [100 microliters] into 0.9 ml): 1/10 x 1/10 x 1/10 = 1/1,000.

Now you could add 1.0 ml of the starting 1/1,000 dilution to1.0 ml of diluent, making a 2-fold dilution (giving 1/2,000).Then remove 1.0 ml from that dilution (leaving 1.0 ml for yourtests), and add it to 1.0 ml of diluent in the next tube (giving1/4,000). And so forth for 3 more serial dilution steps (giving1/8,000, 1/16,000, and 1/32,000). You end up with 1.0 ml of each dilution.If that is enough to perform all of your tests, this dilution planwill work. If you need larger volumes, increase the volumes you useto make your dilutions (e.g. 2.0 ml + 2.0 ml in each step).

Introduction

A Serial dilution is a series of dilutions, with the dilution factor staying the same for each step. The concentration factor is the initial volume divided by the final solution volume. The dilution factor is the inverse of the concentration factor. For example, if you take 1 part of a sample and add 9 parts of water (solvent), then you have made a 1:10 dilution; this has a concentration of 1/10th (0.1) of the original and a dilution factor of 10. These dilutions are often used to determine the approximate concentration of an enzyme (or molecule) to be quantified in an assay. Serial dilutions allow for small aliquots to be diluted instead of wasting large quantities of materials, are cost-effective, and are easy to prepare.

Equation 1.

[concentration factor= frac{volume_{initial}}{volume_{final}}nonumber]

[dilution factor= frac{1}{concentration factor}nonumber]

Key considerations when making solutions:

- Make sure to always research the precautions to use when working with specific chemicals.

- Be sure you are using the right form of the chemical for the calculations. Some chemicals come as hydrates, meaning that those compounds contain chemically bound water. Others come as “anhydrous” which means that there is no bound water. Be sure to pay attention to which one you are using. For example, anhydrous CaCl2has a MW of 111.0 g, while the dehydrate form, CaCl2 ● 2 H2O has a MW of 147.0 grams (110.0 g + the weight of two waters, 18.0 grams each).

- Always use a graduate cylinder to measure out the amount of water for a solution, use the smallest size of graduated cylinder that will accommodate the entire solution. For example, if you need to make 50 mL of a solution, it is preferable to use a 50 mL graduate cylinder, but a 100 mL cylinder can be used if necessary.

- If using a magnetic stir bar, be sure that it is clean. Do not handle the magnetic stir bar with your bare hands. You may want to wash the stir bar with dishwashing detergent, followed by a complete rinse in deionized water to ensure that the stir bar is clean.

- For a 500 mL solution, start by dissolving the solids in about 400 mL deionized water (usually about 75% of the final volume) in a beaker that has a magnetic stir bar. Then transfer the solution to a 500 mL graduated cylinder and bring the volume to 500 mL

- The term “bring to volume” (btv) or “quantity sufficient” (qs) means adding water to a solution you are preparing until it reaches the desired total volume

- If you need to pH the solution, do so BEFORE you bring up the volume to the final volume. If the pH of the solution is lower than the desired pH, then a strong base (often NaOH) is added to raise the pH. If the pH is above the desired pH, then a strong acid (often HCl) is added to lower the pH. If your pH is very far from the desired pH, use higher molarity acids or base. Conversely, if you are close to the desired pH, use low molarity acids or bases (like 0.5M HCl). A demonstration will be shown in class for how to use and calibrate the pH meter.

- Label the bottle with the solution with the following information:

- Your initials

- The name of the solution (include concentrations)

- The date of preparation

- Storage temperature (if you know)

- Label hazards (if there are any)

Serial Vs Parallel Dilution

Lab Math: Making Percent Solutions

Equation 2.

Formula for weight percent (w/v):

[ dfrac{text{Mass of solute (g)}}{text{Volume of solution (mL)}} times 100 nonumber ]

Example

Make 500 mL of a 5% (w/v) sucrose solution, given dry sucrose.

Serial Vs Parallel Dilution

- Write a fraction for the concentration [5:%: ( frac{w}{v} ): =: dfrac{5: g: sucrose}{100: mL: solution} nonumber]

- Set up a proportion [dfrac{5: g: sucrose}{100: mL: solution} :=: dfrac{?: g: sucrose}{500: mL: solution} nonumber]

- Solve for g sucrose [dfrac{5: g: sucrose}{100: mL: solution} : times : 500 : mL : solution : = : 25 : g : sucrose nonumber]

- Add 25-g dry NaCl into a 500 ml graduated cylinder with enough DI water to dissolve the NaCl, then transfer to a graduated cylinder and fill up to 500 mL total solution.